Can you cut 1 Tonne of carbon pollution out of your life?

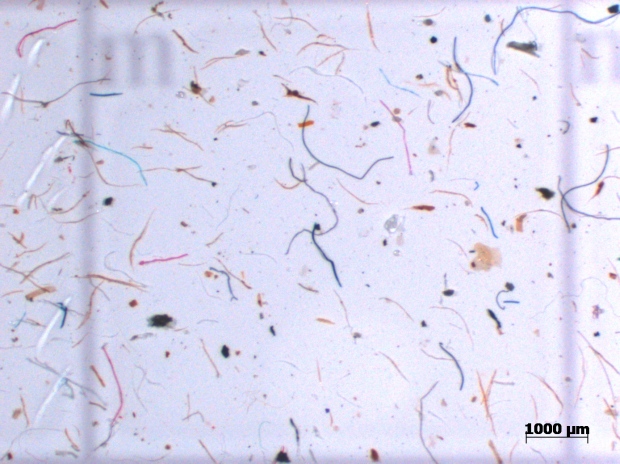

Take the challengePlastic fibres in our clothes are damaging waterways, marine ecosystems and our foodchain. As we wash our clothes, fibres travel all the way into lakes, rivers and the ocean where they find their way into the stomachs of fish and other wildlife.

To what extent are they a problem?

To put it into perspective, 85% of the human made debris found on shorelines around the world is made up of microfibres. These fibres do not only affect fish, but also zooplankton, benthic organisms and mussels, which find these fibres stuck in their intestinal tract, and thus suffer from non-biodegradable gut blockage. When organisms ingest these plastic microfibres they are given a false sensation of satiety which affects their ability to process real food. This deceptive sense of fullness often results in starvation. Medals fish in Japan have been found to suffer from liver stress when exposed to microfibres. And although mussels and oysters are particularly susceptible to microfibre consumption, swordfish, bluefin and albacore tuna are other commonly consumed species which suffer the consequences of this kind of pollution.

As a result, humans are directly impacted by the effects of microplastic consumption. When we consume these marine species, we are ingesting an unknown quantity of toxic compounds.

In addition to the fish that humans consume, microplastics have also been found in sea salt that is used for food seasoning. According to a study, between 550 and 681 particles of microplastic can be found in just one kilogram of sea salt. The most abundant type of microplastic found in sea salt is polyethylene terephthalate, more commonly known in the textile industry as polyester.

Scientists are still trying to develop a reliable and repeatable method for reporting the impact of microplastic pollution and its impact on human health and marine ecosystems. Although the extent to which these fibres pollute is yet to be determined, its negative impact is not questioned.

What can we do about microfibre pollution?

To solve this problem, it's important to look to a combination of solutions on both industry and consumer levels. We can urge textile brands to review the impact of their fabrics, pressure washing machine companies to install appropriate filtration devices and municipal water management to investigate better ways to filter waste water.

On the consumer end, we can each take action to reduce the amount of plastic microfibres entering the ocean, starting today. Here's how.

- Pay attention to your clothes' labels. Synthetic fabrics, most often found in fleece garments, leggings, and athletic wear are largely to blame for the release of these plastic fibres into waterways. Although natural fabrics also shed microfibres, they break down much quicker than their synthetic counterparts which can take centuries to degrade. Acrylic clothes release 730 000 synthetic particles per wash, five times more than polyester-cotton blend fabric and 1.5 times more than polyester. Older synthetic jackets shed almost twice as many fibres as new jackets. Next time you shop, choose natural fibres like cotton, linen, silk, cashmere, hemp, jute and wool which will eventually break down.

- Wash as little as possible. Instead of washing, hanging clothes out in the sun is an effective way of killing bacteria that causes odour. When clothes are dirty, spot-wash as much as you can and make sure to use a cold wash setting when using a washing machine.

- Use a filter bag. Although filter bags for microfibre pollution are still very new on the market, they're a huge step in the right direction for stopping this global problem. A study conducted by UCSB found that putting synthetic clothing into the Guppy Friend filter bag before washing, either by hand or by machine, can stop between 90 to 95 percent of microfibres from being released into waterways. During each wash, microfibres are collected within the bag and can then be disposed of responsibly.

Most importantly, if we all spread the word about microfibre pollution, we can encourage further research into the problem and make polluting industries accountable.Written by Anna Calderon

Anna Calderon is a Master's student at Concordia University in Montreal. She works as a researcher for the Lab of Latin American Studies and serves as executive director of Say Ça!, a non-profit organization which provides support to refugee youth.Read this next: Is Secondhand Shopping Really As Sustainable As We Think?

We're in a climate emergency and it's going to take all of us to get out of it. That's why 1 Million Women is building a global community of women committed to fighting climate change with our daily actions. To join the (free) movement just click the button below!