In his book 'Eating Animals', Jonathan Safran Foer recounts the story of his grandmother fleeing persecution in Nazi Germany: "The worst it got was towards the end. A lot of people died right at the end, and I didn't know if I could make it another day. A farmer, a Russian, God bless him, hesaw my condition, and he went into his house and came out with a piece of meat for me." "He saved your life," Jonathan remarked, but his grandmother would not eat the meat. The meat was pork, and the pork was not kosher. "But not even to save your life?" Jonathan continued. His grandmother replied, "If nothing matters, there's nothing to save."

Reading these words, I reflected on my own situation of trying to live sustainably with a chronic illness. In a world bent on productivity, with success measured by GDP (gross domestic product), the market value of the goods and services produced in a year, the lives of those suffering from chronic health problems are often deemed less productive and therefore less worthy. When the sustainability narrative invites us each to reflect on our own environmental burden, it can make individuals feel not only worthless but even damaging. But sustainability is about more than the environment. It's about what matters to every one of us, our values, our traditions, our interests and our happiness. "If nothing matters, there's nothing to save."

I therefore try to reduce my impact on the environment with the caveat that any changes I make do not negatively affect my health. For me, this means buying loose fruit and vegetables and shopping for other pantry staples in a local zero-waste shop, but looking past the pile of non recyclable blister packs which I send to landfill each week after filling my pillboxes. It means switching to a bamboo toothbrush, but continuing to use the high-fluoride toothpaste prescribed by my dentist because of my health problems. It means not feeling guilty about my carbon footprint when fatigue or risk of infection prevents me from travelling by public transport to hospital appointments and other commitments. It means using social media to voice my concerns when my health prevents me from attending protests. It also means recognising my privilege in being able to make all the changes I have made.

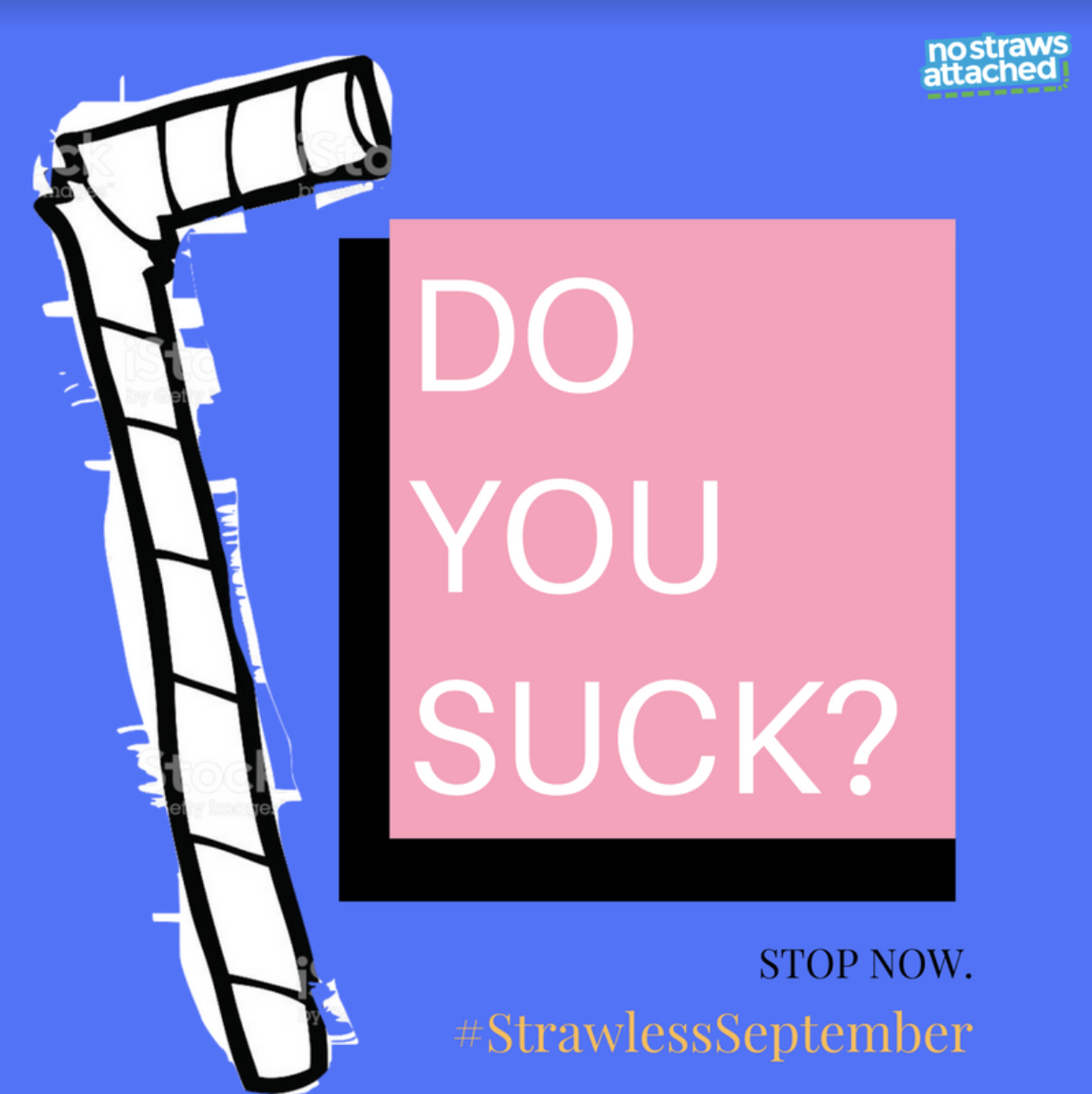

Legislation plays an important role in protecting the environment. After a 5p levy on plastic bags was introduced in the UK, distribution by large supermarkets fell by 95%. A public consultation found that the "vast majority" of respondents welcomed an increased levy of 10p. The recent ban this month on single-use plastic straws has proved more controversial. Despite an exemption for those with medical need, for whom plastic straws will be available on request at pubs and restaurants and available to purchase from pharmacies, disability campaigners are concerned that the new legislation will result in scapegoating of disabled people for continued use. Indeed campaigns against single-use plastic often capitalise on shaming consumers into submission, asking, for example, "Do you suck?".

[Image: Supplied by the author, from the 'No Straws Attached' Facebook Page]

As such initiatives become more commonplace, it is important to consider the ableist foundations of anti-plastic legislation, which is founded on the premise that such items are not really necessary, or that more sustainable alternatives will fit the bill. For people with disability, this is not always the case. Those with swallowing problems, due to conditions such as muscular dystrophy, often rely on the flexibility of the plastic straw. For others who are at a high risk for infection, the single use element is essential to ensure safe consumption. Exemptions in legislation are important, but these exemptions must translate to public opinion. The legislation exists to restrict unnecessary single-use plastic, not to restrict access for those who need it. After all, it is estimated that plastic straws account for only 0.03% of ocean plastic, compared to the 46% from discarded fishing nets.

Indeed, such considerations bring us back to the question, what is it all for? We must be aware of the dangers of the utopian underpinnings of environmental activism. When we strive for perfection, there will always be a shortfall—a human shortfall—to correct, for example, the disabled consumer with a plastic straw. Christiana Figueres and Tom Rivett-Carnac, key instigators of the United Nations Paris Agreement and co-founders of Global Optimism, recommend an alternative approach — stubborn optimism. Where utopia describes a place, optimism describes an attitude. After all, rather than creating a zero-waste, carbon-free, vegan utopia, surely the ultimate aim of sustainability is to create a safe and comfortable future for all living beings. UK politician David Lammy recently stated that: "We need a recognition that the climate movement is not only about protecting the planet. It is primarily about caring for the people [and, I would add, other living beings] who live on the planet." Environmental justice must, by definition, be inclusive. There can be no environmental justice without social justice. Indeed, environmental justice is a form of social justice.

By Catherine Dixon

Catherine is a second year music student at Merton College, Oxford University. She has a keen interest in sustainability and social justice. Catherine enjoys walking her dog in the local countryside and exploring new vegan recipes.